Population

According to thesciencetutor, Zimbabwe has a population density of 37 residents per km 2 (2019), but depending on the colonial land distribution legislation, the population is very unevenly distributed. Large parts of the more upland areas in the middle parts of the country were reserved for European-owned large-scale farming and are therefore still relatively sparsely populated. By contrast, the more peripheral, and less fertile, areas allocated to African settlement show relatively high population concentrations. In the latter areas, the increased pressure due to high population growth has led to increased supply problems with consequent soil degradation in the form of erosion damage.

About 32 percent of the population in cities (2019), of which Harare (1.5 million residents, 2013), Bulawayo (653,300) and Chitungwiza (356,800) are the largest.

Of the Zimbabwean population, about 82 percent are Shona-speaking peoples, while the area in the far south is inhabited by South African immigrants from Ndebele, which comprises 14 percent of the population. The white population, mainly descendants of British and South African immigrants who began to flow into the country in the 1890s, has largely emigrated since the beginning of the 1980s. They currently amount to just under 45,000. At the far north there are 300,000 people belonging to the Tsonga people. There is also a small group of san (previously named bushmen) of 1,200 people, who are trying to live as hunters and collectors. However, discrimination, poverty and legislation, in many ways, make their lives more difficult. The country also has about 68,000 swazi.

The Shona-speaking peoples consist of the ethnic subgroups kalanga, karanga, kore-kore, manyika and zezuru. These groups have a similar culture with clear roots in the prehistoric kingdoms that were described as early as the 16th century by Portuguese traders. Best known of these kingdoms is Monomotapa, which had its heyday in the 17th century, and its predecessors in the area of Greater Zimbabwe.

The Shona people still consider themselves to be part of the local kingdom where the sacred chieftain, in consultation with his spirit medium, bears the responsibility for rain and fertility in his region. The Shona people, who traditionally have a strictly patrilineal family structure, attach great importance to the male ancestors – both the royal ancestors, who provide rain, and the “private” who are responsible for the well-being of the individual family. In addition, medicine men are often hired for sessions with healing and spirit crew.

The Shona people’s livelihood was previously based on millet (“man’s crop”) and root fruits and vegetables (“women’s crops”). In addition, most families keep a few cows near their compact “family villages”. Today, when most working-age men have wage jobs in urban centers or on European farms, women do both cows and agriculture, and the millet has been replaced by corn.

The everyday life of the Shona people has a strong ceremonial touch when members of different generations and genders meet. The role of father (baba) is emphasized ritually in hierarchical family life, as well as in myths and sayings. Behind the scenes, however, the wife/ mother has the power over the children and now also shows great enterprise.

The Ndebele people in the south are mainly descendants of warriors who deserted from Zulu Chief Shaka’s army in the 1820s. In principle, they have almost the same (but less ceremonial) family organization and livelihood as the Shona people, but they place more emphasis on livestock management.

Their culture in general testifies to the kinship of the Nguni people, mainly Zulu, Sotho and Tswana, from which their ancestors were recruited into the Shaka army. Ndebele has created a stratified society with three social classes. At the top of the rank is zansi, who consider themselves Zulu descendants, including some of Sotho descendants and below loswi or holi, who are regarded as descendants of the urinals.

Language

English is the official language and predominates in administration and mass media, but is spoken as a native language of no more than 1% of the population. The largest indigenous languages are Shona (50–75%) and Ndebele (10–15%), both of which are Bantu languages. Another dozen bantu languages are spoken by smaller groups.

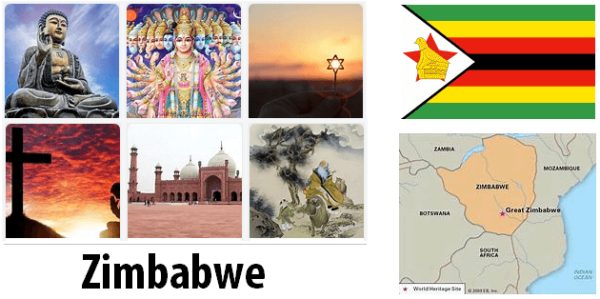

Religion

Today, over 80% of the population is estimated to be Christian, and more than half (46%) of them belong to an independent church that can refer to themselves as Pentacostal, Charismatic, New Charismatic, Apostolic or as a Zionist Church. The proportion of the population who are Protestants, e.g. Baptists, Methodists, Lutherans, Presbyterians and Congregationalists amount to just over 20%. These communities began to operate in the country during the second half of the 19th century.

The first Christian church to establish itself in the country, however, was the Catholic. The Portuguese Jesuit missionary Gonçalo da Silveira arrived in the country in 1560. He was assassinated the following year, but Catholicism continued until 1667, when all Catholic activities in the country ceased. The Catholic Church returned in 1890 and today it is estimated that about 14% of the population are Catholics.

Among other Christian communities in the country are the Seventh-day Adventists, who have a membership of just over 6% of the population. The proportion of Muslims, who mainly live in the cities, is just under one percent and those belonging to Bahai are about the same.

Traditional indigenous religion is of great importance in Zimbabwe. The proportion of followers is stated to be one-fifth of the population, but beliefs are shared by many more because the syncretistic elements are large (see syncretism). During the struggle for majority rule, ancestral cult and mediators with the spirit world had great political significance.

According to the secular constitution and other laws, religious freedom is guaranteed. Zimbabweans have the right to choose and change religion. They also have the right to practice their religion both privately and publicly and to propagate it. Criminal law prohibits witchcraft intended to harm a person. Under the same laws, it is forbidden to persecute and kill medicine men and to falsely accuse someone of being a witch/medicine man. In many official contexts, Christian prayers that are not associated with any specific community are being prayed for. According to the law on public order and security, the government happens to intervene in larger public prayer meetings that are considered to have political content, ie. in front of criticism against the ruling party ZANU-PF.

The country’s political elite are often closely associated either with one of the established Christian traditional churches or with a Pentecostal church. Some Christian groups, especially apostolic ones, support the ZANU-PF.

In the upper secondary schools teaching is given about Christian communities and also about other religions. About 30% of the country’s primary and secondary schools are run by some church or congregation. These schools are free to decide their own curricula, which also applies to the Islamic, Jewish and Hindu schools.

The following days are religious national holidays: Easter Day and Christmas Day.