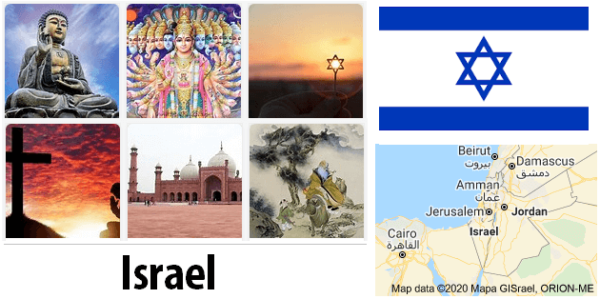

According to thesciencetutor, there is full religious freedom in Israel, but the majority of the population (outside the occupied territories of 1967) belongs to Judaism (about 80%). It is approx. 15% Muslims (mostly Sunni Muslims), 2% Christians and 1.6% Drusters. In the West Bank, Muslims (mostly Sunni Muslims) are in the majority (75%), while Jews make up approx. 17%, Christians and others approx. 8%. In the Gaza Strip, the Muslims (mostly Sunni Muslims) make up approx. 99%.

Israel is a secular state, and there is a distinction between state and synagogue, but Jewish law (Halaka) applies in some areas, e.g. family law. All Jewish marriages and divorces must be religious and approved by the Overrabbinate, or possibly dealt with in a religious court. The Sabbath (Saturday) and other Jewish holidays are religious holidays.

Orthodox Jews have formed various religious parties that often have great influence in political life. Important areas for the religious parties are school politics and settlement policy, and they want public observance of the Sabbath.

Religion in Ancient Israel

Ancient Israel is a common term in the Middle East area inhabited by Biblical Israelites. The extent varied over time, and the population also included residents of different ethnicities. The time period you include also varies. It is common to count from approx. 1200 BCE to around 300 AD. But in order to gain a connection in the history of the Israelites (Jews), one often also reckons right up to the temple in the fall of Jerusalem in the year 70 CE.

In the research, the term israeli religion is often used to refer to the religion of ancient Israel in the time before the Babylonian exile (586-538 BCE) and “the Second Temple period” or “early Judaism” from the time of exile up to the emergence of rabbinic Judaism. Christian bible research has often used the term “late Judaism” for the period from around 200 BCE. to 100 AD, which is misleading, since it was during this particular period that rabbinic Judaism began to take shape. Jewish tradition uses the terms Am Israel (the people of Israel), Jews and Judaism throughout the period, which implies a notion of continuity.

Sources

The religion that was practiced in this area early on is today a topical and contentious area of research. It is not easy to reconstruct what people in ancient times really believed and practiced. The sources do not give a clear picture and can be interpreted in different ways. Earlier research was largely based on the texts of the Hebrew Bible and was characterized by theological interests and views. Today, the religion of Israel is being investigated on par with other ancient religions in the Middle East. Archeology has become increasingly important.

There is now a broad consensus that the transition from polytheism to monolithy (where one worships only one deity, but accepts that other peoples have other deities), to pure monotheism may have taken a long time and been associated with many confrontations and setbacks. According to the biblical texts written by representatives of the official religion, YHVH (Yahweh) was to be the only god of the Israelites, but right up to the Babylonian exile (586-538 BCE), the people are constantly accused of worshiping other gods as well. Archeology describes this.

Bible texts

The Hebrew Bible One is still the most important source of our knowledge of the early evolution of the official religion. The Bible texts give the impression that a strong Israelite people wandered into their new land with their own unifying religion, ethics and way of life that was in stark contrast to both the religious conceptions and way of life of both Canaanites and neighboring countries. In Bible research, too, it has long been common to assume that the early religion of the Israelites was more high-ranking and ethical than the neighboring countries’ religions.

The texts include poetry, myths, legends, descriptions of what appear to be historical accounts and not least laws. But the texts are not historical in the modern sense of the word. These are ideological texts that have been created over a long period of time. They are written by learned men and convey a picture of their views on the deity, the people and the history. The laws concerning women are therefore characterized by men’s perceptions and interests. The texts are also strongly influenced by the theological views of the later editors.

Both Jewish and Christian tradition were shaped at a time when no one questioned the reliability of the Bible as a historical source. There was broad agreement that the books of Moses were the result of a direct divine revelation, and that they were written down by Moses himself. The historical books were perceived as a description of actual events. It was not until the Enlightenment era of the 18th century that biblical scholars began to study the books of Moses with critical eyes and to ask who wrote them and when they were written and edited.

Modern biblical science (the multiple-source hypothesis) believes that the books of Moses are composed of four written sources, from different times and from different environments. The age of the other texts is also disputed, not least because Bible scholars have been influenced by their theological ideas. For example, many Christian theologians (such as Wellhausen) have been concerned with highlighting the Prophets’ ideas at the expense of the Law (Torah One). In the first half of the 20th century, many scholars (the myth-rite school) believed that the poems in the Book of Psalms could tell us a lot about the ancient Israelite cult and, in this context, tried to reconstruct different parties. These ideas are not widely used today.

Although many of the later Bible texts contain laws, stories, and songs (hymns) that may date from early prehistoric times, we do not know to what extent the narratives and laws were known among ordinary people across the country. People had no Bible, and literacy was hardly widespread in the early days. We do not know to what extent the religious conceptions of the authors and editors also reflected the beliefs and practices of the rest of the population. This is largely true of women and their religious lives. Here archeology can provide answers other than the texts.

Nor do we know when the story of the revelation at Sinai became widely known, or when the various and detailed laws of purity found in Leviticus were practiced by all the people. It has been suggested that it may be as late as in connection with the Babylonian exile.

Archeology

In order to know something about what the people really believed and practiced, we must use both archaeological finds and knowledge of neighboring religious beliefs. While former archaeologists were most concerned with finding remains for large buildings, such as city walls and palaces, and often using the Bible as a tool to date the findings, the later decades of archaeologists have also been interested in examining ordinary people’s houses, tombs, and holy sites. The small arts, which include amulets, stamps, jewelry and statuettes give us a diverse picture. In a Jewish family grave from the end of the 600s BCE. has, for example, found amulet is with texts that correspond well with known biblical texts, which 4. Genesis, from 6.24 to 26. (“The Lord bless you and preserve you…”), which is still used in both synagogues and churches. But texts have also been found to indicate that Yahweh may have been associated with female powers.

The smaller objects are also often decorated with pictures showing that the Israelites were well acquainted with neighboring religious symbols. Even those affiliated with the official religion took advantage of them. For example, during the reign (from about 1000-586 BCE), many of the king’s officials used Egyptian symbols, such as urea snakes, on their personal stamps. In the last centuries before the exile, Assyrian symbols also became popular. We have no great statues or images of God from Ancient Israel, but this was not a culture without images.

Therefore, when attempting to give a picture of faith and practice in ancient Israel before the exile, one must distinguish between the biblical texts’ ideal picture of the official religion and the “foreign” religious forms the authors condemn, but which they nevertheless admitted had both in court and in the popular religion.

The official religion

Bible texts

The Book of Genesis portrays the ancient history of the Israelites as a family story, in which Abraham’s ancestor makes a covenant with a deity and rejects all his ancient gods. Both Jewish and Christian tradition consider Abraham the first monotheist. The story continues with the story of how Abraham and his family migrate into Canaan’s land.

The next crucial event is the story of how his great-grandchild, Joseph and his brothers, end up settling in Egypt, where they eventually become slaves (Genesis 37-50. Then follows the famous tale of the escape from Egypt and about how the tribes of Israel become one people who gather in a religious-political covenant and make a covenant between and with the god Yahweh, at Mount Sinai (Exodus 19 ff.) Yahweh promises to protect and help his people, against the fact that the people, for their part, assume a number of obligations, both culturally and ethically, and the revelation at Sinai and the Ten Commandments is the foundation of both Jewish and Christian law and ethics to this day.

However, neither Abraham’s wanderings, the Israelites’ stay in Egypt, nor their long wanderings in the Sinai desert can be confirmed by non-biblical sources or archaeological finds. However, this does not exclude that there may be some historical core to the stories. However, no researchers believe that there may have been an exodus to the extent or in the form the Bible texts describe.

The Bible’s description of Sinai legislation cannot be used by research to establish which religious notions were widely known at the time when it was growing up in an Israeli highland community on the west side of the Jordan River (c. 1200-1000 BCE). There is also no agreement on where the new inhabitants came from. The most common belief today is that there must have been a redistribution of Canaan’s own population and immigrant groups (tribes). Many scholars, however, accept that at least some of the groups that settled in this area came from Egypt, perhaps over a longer period of time, and that these may have had their own god and their own traditions. It is common to assume that such an emigration may have occurred in the first part of the 13th century BCE.

Yahweh

Jewish and Christian tradition teaches that Yahweh is eternal and all things create. According to Exodus 3.14, the very “name of Yahweh” dates from the time of Moses. YHVH is not strictly a proper name, but can, according to the Bible text itself, be translated with “I am who I am” (Exodus 3:14). The background of God is uncertain.

The original pronunciation of the god-name JHVH in biblical times is unknown today. But inscriptions show that the name was known, often in the Jahu version. We also know that in the time of the Second Temple (about 515 BCE to 70 BCE), this name of God was pronounced only once a year, by the high priest at Yom Kippur. (Where YHWH appears in the Hebrew text, Jews read the name as Adonai [my, or our Lord]).

According to modern research, Yahweh has many features in common with a typical Western Semitic storm and war god, but he is also associated with volcanoes, fire and smoke (Exodus 19:18). This is special to this deity. Another etymological meaning may have been “He blows”. Many now believe that the god Yahweh originated in Midian, the area that is now part of southwestern Jordan and northwestern Arabia. In the Middle East it was only in this area that such natural phenomena existed at this time.

It has also been claimed that the god Yahweh could be a further development of the Canaanite god El. The Bible texts also use the name Elohim (plural of the Semitic word for god) and also other more descriptive terms, such as Elyon (the High), Shaddai (the mighty) or Rahum (the merciful). He is also Lord, adon. Norwegian Bible translations most often use the Lord. The different designations indicate that these have been different environments.

The Bible texts provide many different images of this god. While early texts tell of a god wandering in the garden (Genesis 3: 8), other texts give a picture of one who is separate from this world. He lives in heaven, and when he appears, nature is in turmoil (Psalm 18). The book of Psalms and several of the prophet texts indicate that he was thought to be surrounded by divine beings. He is often called Yahweh Sebaot (Zevaot), the god of armies, with reference to heavenly beings in his following (Psalm 89, Amos 6). He reveals himself and acts through historical events. He is also a god of war, helping his people in their battles against the enemy. He is holy and separate from all that is profanet, but also the one who helps and protects the individual. In that capacity he is also characterized as a shepherd (Psalm 23 and 103). Eventually, Yahweh is considered king, not only lord of his own chosen people, but ultimately king of all peoples.

According to the Bible texts, Yahweh creates life alone, and not in interaction with female forces as was customary in Middle Eastern mythology. However, the wisdom literature (Proverbs, Job, and the Preacher), which has much in common with similar literature from both Egypt and Mesopotamia, contains texts that may be interpreted as Wisdom, which is here described as Yahweh’s first creation, in certain circles or periods, may be been perceived as a kind of goddess (Proverbs 8–9). (Both the Hebrew original text and Jewish translations use throughout the feminine pronouns and verb forms.)

It is believed that it was mainly the prophets who formed the idea that Yahweh was not only the God of the Israelites, but also the creator of the entire world and of all people. This basically makes all people equally valuable. There was an idea that what one does to one’s fellow human beings is one to God, which has consequences for both ethics and moral laws.

The hymns can be divided into three groups. A group of hymns praise Yahweh, as Lord, King and Creator of the world (Psalm 8, 103, 104, 135), others are public lamentations used either when war or other misfortune threatened the country, or when the king or another person was ill or suffering (individual lamentations). There were also thanksgiving hymns that were used when the people or individual were rescued from distress. A separate group of hymns is often called historical since they mention events in the lives of the Israelites (Psalm 44, 80, 105, 114).

The cult

The religious cult was intended to strengthen the national community, and to maintain a demarcation from the surrounding ethnic groups. This may have been important early on. For example, no bones of pigs have been found in Israeli settlements from the period we call the Judges (c. 1200–1030 BCE). We do not know much about the official religious activities during this formative period, but archaeological excavations have shown that there were several smaller cult sites around the country. These were often located at heights in the landscape, and may have been used for both Yahweh cult and more alternative forms of worship.

First in King Solomon’s reign (c. 970–930 BCE), a larger cult site, a temple, was built in Jerusalem. The Bible’s description of the temple’s form and decoration may seem overwhelming, but its design seems to have had many commonalities with what was common in both Canaan and Syria at this time. The texts describe a building that consisted of a vestibule and two inner rooms – one sacred room and the most sacred. In the holy stood candlesticks, the altar of incense and a table with spectacles. In the holiest room stood the ark of the covenant, a coffin that also symbolized Yahweh’s presence in the temple. The great altar of burnt offering stood out in the porch or front yard.

The decoration described is also now known from other buildings in the area (1 Kings 6, 21–29). Cherubs, mixed creatures with lion bodies, human heads and wings, were used as symbols of the deity in many Middle Eastern countries from the third millennium BCE. Palm trees and lotus flowers are also well-known common symbols. The description of the temple is marked by the authors ‘and the editors’ notions of King Solomon’s wealth and power. His real temple may have been somewhat simpler.

As for the official religious acts, the Psalms can give us some information. Some scholars have suggested that a significant portion of the cult lyric, such as those under the name of “David’s Psalms,” may be the poems of the singers and musicians who worked at the Temple in Jerusalem. They have many similarities to both ancient Egyptian and Ugaritic hymns. However, there is still no consensus, either on the age of the individual hymns, or whether certain hymns can be written by one particular person. Some may date from the early royal period, but many were written in the time after the Babylonian exile.

In the psalms it is a matter of going to the Lord’s house or altar, attending the sacrifice and feasting at the temple. As in the other cultures of the ancient Middle East, sacrifice was the most important cult. The idea behind the sacrifice was that it should either be a gift to the deity, or also atonement for guilt. Most often the animals were sacrificed, but they could also be sacrificed by the crop. Small incense altars have also been found at smaller cult sites in the area. The service was accompanied by music and singing.

The three major pilgrimages, when the people would come up to Jerusalem, are all related both to agriculture and to history. Pesach, which was celebrated in the spring, marked the beginning of the barley harvest and was also celebrated in memory of the liberation from slave life in Egypt. The weekly feast (shavuot) was celebrated seven weeks later when the wheat was ready for harvest, but also in remembrance of God revealing himself to Moses on Mount Sinai. The booth party (sukkot) marked the wine harvest. Observance of the Day of Atonement, yom kippur, is commanded in Leviticus 23, 27–32, and these rituals were also celebrated in the temple. Otherwise every 7 days, was the Sabbath(Shabbat), properly marked with special sacrifices and prayers. Despite the fact that all the people were encouraged to come up to Jerusalem for the great holidays, we must expect that most people never had the opportunity of such a long and arduous journey.

Priests and Prophets

The Bible texts state that it was a firm and hereditary priesthood tasked with leading the sacrificial acts and worship. The task went on a lap. The priests traditionally descendants of Moses’ brother, Aaron, could not own land. This also applied to the Levites, who performed at the temple. Priests and Levites were therefore entertained by the tithing of the people. They were also to teach the people and keep watch over the temple’s other officials, singers, musicians and cult prophets. Deviations from official doctrine were hardly tolerated by these.

Prophets could also be associated with the temple and stand in the service of the king. They were called upon when important decisions were to be made, such as war, when, according to the Bible texts, they were commissioned to predict the outcome of the impending conflict. Probably the priests themselves often acted as prophets. Early on, priests and prophets were also associated with the local official cult sites around the country. However, according to 2 Chronicles 34 and 2 Kings 22-23, King Josiah (in about 622 BCE) tried to remove what was considered foreign cult, and carried out a consistent centralization of the Temple of Jerusalem, without fully succeeding. All priests and prophets were now associated with the temple in Jerusalem and subordinate to the priests there.

According to the Bible texts, it was the prophets who fought most strongly for the pure Yahweh faith (see Elijah’s fight against the god Baal and the goddess Ashera, 1 Kings 18). We already find these monotheistic ideals in the prophets of the eighteenth century, Elijah and Elisha, but they have hardly had any impact in all parts of the people until many hundreds of years later. Prophets like Isaiah and Amos(7th century BCE) emphasized Yahweh’s power and power, and the demands he had the right to make. The prophets were also keen to emphasize that the sacrifice did not work in itself, so to speak automatically, but had to be followed by ethical mischief, social thinking and caring for fellow human beings if one would expect God to accept them (Amos 5).

In the time of the exile, the prophets Ezekiel and Jeremiah acted as both preachers of God’s punishment and the destruction of the people. The people had failed, worshiped other gods and goddesses, and the calamity had to come. By regretting and asking for forgiveness, it was still possible to obtain forgiveness. There was also an idea of the future king of the Messiah, of the seed of King David, who was to lead a new and independent Israel, where all the people would gather again. This gave rise to later Jewish messianism.

People religion

The transition from monolatry to pure and reflected monotheism has, according to judgment, taken a long time for large sections of the population. Both the Bible texts and archaeological findings show that there must have been a gradual change, with constant confrontations with earlier forms of religion. This was also a time when the religious dimension of sexuality, the interplay between the female and male aspects of creation, was to be removed. This is about a time when all divine power was to be united with one transcendent god. Yahweh, unlike the neighboring deities of neighboring countries, is not a sexual being, yet appears as “man” in the Bible texts. Thus, a “male” deity should now take over the former responsibilities of the goddesses.

Both the Bible texts themselves and archaeological finds show that in many circles the ancient gods of the area still had a meaning right up to the fall of Judah. Many also indicate that female deities were not easily removed from popular religion. Today, many scholars also believe that the Israelites, or some of them, may have had a notion that Yahweh also needed a female power by his side, as other high gods in the Middle East had.

In the past, it was almost of course assumed that it was mainly Astarte who was associated with what the prophets and writers regarded as apostasy from the true faith. Where the word or name a/Ashera (Hebrew does not have uppercase and lowercase letters) appeared in the Bible texts, it was translated with “grove” or replaced with Astarte. This was before the Ugaritic texts showed that Ashera was the “mother of the gods” in Ugarit. Many now believe that it is likely that the Ashera we encounter in the Bible texts, in iconography, and in inscriptions may be an heir to the Canaanite goddess Ashera, symbolized in the form of a crafted wooden stick, a living tree or an image of the goddess. Ashera is mentioned 40 times in the Hebrew the text, and it is clear that her cult is highly undesirable among the scholars. She is both “cut down,” “destroyed,” and “burned” (2 Kings 23: 6).

Of particular interest are also the many small pillars of terracotta found in private Jewish homes from the King’s period, especially from the 7th century BCE. More than a thousand of these have now been found. Such figures, as well as small horses, birds and miniature furniture, incense altars and Egyptian-inspired amulets have also been found in smaller and unofficial cult sites. We now also have several inscriptions which mention “Yahweh and his a/Ashera”, partly accompanied by drawings of male and female beings. This may indicate that “Yahweh and his a/Ashera were a kind of well-known and accepted blessing formula.

The Bible texts show that Canaan’s ancient gods were also admitted to the courts in Jerusalem and Samaria, so it would be wrong to designate this as pure “people’s religion”. Many of the ancient kings of Israel were accused of worshiping gods other than Yahweh. Already King Solomon must have been tempted to build altars for foreign gods and worship both Astarte and Milkom (1 Kings 11, 5–8). The kings of the later Northern Kingdom, Israel, receive particularly poor reputation, and Queen Jesabel is condemned, among other things, for entertaining both Baal and Ashera prophets. In the reign of King Joakas (818-802 BCE) there must have been an Ashera (perhaps a statue) in Samaria (2 Kings 13.6).

Much may also indicate that the male gods of the surrounding lands had also been admitted into the temple in Jerusalem (Ezekiel 8: 7-12). In Ezekiel 8.14 we can read about women who “sat and wept for Tammuz “, the Mesopotamian god who was the companion of the goddess Ishtar. In Jeremiah 44,15-19 we hear that cakes were baked in the streets of Jerusalem in honor of the Queen of Heaven, which several scholars believe may be a designation of a fusion of the Mesopotamian goddess Inanna/Isthtar and Astarte, not least because of Assyrian texts show that cakes were offered to Ishtar. In Judah, this seems to have been a family cult in which women had a special role. To end this cult, according to the people, must have been what led to hunger and the lack of weapons (Jeremiah 44: 18-19).

We do not know the extent to which the worship of female deities may have characterized the more official cult, but much indicates that in the home and the community, her role may have been important. We also do not know whether there has been any regular domestic cult, but the shape of the female figures indicates that they have been arranged in a niche or similar. It has been common, both in the Bible texts and in research, to claim that it was the women who introduced or practiced such a non-regulated cult, and that precisely women felt a need for a female deity in life’s difficult and dangerous situations, such as births., illness and toddler periods. However, it is unlikely that women could practice a cult in the home that the man was not aware of.

The king

The first king, Saul, was deployed by the prophet Samuel during a time of crisis. His successor, King David, is described as the one who made Ancient Israel a great power in the area. According to 2 Samuel 7: 12-13, David must have been promised by Yahweh that his successors would be kings of Israel forever. His successor, King Solomon, gained a reputation as rich, wise and powerful. The texts give the impression that the people should honor their king, but that the king was also expected to abide by the Law (the Torah), he was not omnipotent. Deuteronomy 17: 14-20 warns against kings who take too much power, hold too many wives or acquire too much wealth.

The image of the king is not uniform. We do not know how ordinary people regarded their king. Several hymns may indicate that the king, at least in some circles, was considered the “son” of God, and was thought to be imprisoned on the throne of Yahweh (Psalm 2 and 110). The king should ideally be the foremost religious leader of the people. He was mashiah (gr. Messiah)), the anointed one, which may refer to a ceremony performed at the Gihon source in the valley of Kedron in connection with the coronation. Some of the hymns may be interpreted as if both the nature and the people were protected by the king and the godly power he represented (Psalm 72). Psalm 45 can also be interpreted as if the king was more than an ordinary man, that he was divine. This view was particularly widespread within the field of religious-historical research called the myth-rite school.

Other texts give a quite different picture of the kings relationship to their people and to the official religion. According to the Bible texts, King Solomon was already accused by the people of introducing forced labor in connection with his major construction projects. He is also accused of letting his foreign wives seduce him into disbelief and foreign religious practices. After King Solomon’s death, when the land was divided into the southern kingdom (Judah) and the northern kingdom (Israel), many kings took power through war, removing competitors and intrigues. The kings of both countries held great harem, gathered wealth and entered into political marriage with daughters of the rulers of neighboring countries. These foreign women are often accused of having led their husbands away from proper faith and practice.

Life after death

Life after death was not an important part of early Israelite religion, the early Bible texts give the impression that the dead were “sleeping” in the Kingdom of Death (Genesis 37, 35). This was a kind of shadowy realm, a notion that was also prevalent in Mesopotamia. However, several scriptures indicate that the dead had some form of existence and could be reached. The Book of Exodus contains a ban on grave cult (Deuteronomy 25:14), but the many finds of articles of use in ancient Israelite tombs may mean that the people’s religion hoped for a more active life in the Kingdom of Death, and that family members therefore equipped the dead with both food and objects. Real notions of bodily resurrection are met only in time after the Babylonian exile.

Exile

When the Northern Kingdom, Israel, was destroyed in 722, a large proportion of its inhabitants were exiled to Assyria, where most of them were eventually assimilated. Other groups of people were moved into the former Israelite area. Judah continued to exist as its own state for more than a hundred years. The exile in Babylonia (586-538 BCE), on the other hand, became a kind of turning point in the evolution of the Israelite religion. From now on we are talking about Judaism, since it was the people of Judah who carried on the traditions.

The temple was destroyed, the temple cessation ceased, and the upper class, the priesthood and the scholars were exiled to Babylonia. Many had also fled to Egypt, where many Jewish communities eventually emerged. Prophet one Jeremiah and Ezekiel claimed exile was God’s punishment of his people, but that it could also be the start of a new beginning. The prophets promised that if the people repented and promised to turn again to the right faith and practice, God would give them another opportunity. Yahweh was no longer perceived as the only national god of Israel. He could use other peoples, like the Babylonians, to punish his own people. He has now become the God of the entire universe.

We have little concrete information about the religious life of the Jews in Babylonia. According to Ezekiel 1.1–3, there was a Jewish community by the river Kebar from the year 597 BCE, when a large part of Judea’s upper class was brought to Babylonia. Ezra’s book also mentions several places that had Jewish communities. All indications are therefore that the abducted Jews were allowed to settle with their own. Without a temple as a central gathering place, it became even more important than before to retain one’s identity and one’s religious notions and laws. It again became important to separate oneself from others.

Many believe, therefore, that it was in Babylonia that they began to gather in an early form of assembly houses (synagogues), to study sacred scriptures, pray, and sing hymns, but no remnants of such were found. However, common meeting places may have been used by prophets and scholars who passed on the doctrine of the One and Almighty God. You could also put more emphasis on practicing your own laws on a daily basis, both when it comes to family matters, food and holidays.

Homecoming

When King Persian King Cyrus allowed the Jews to return to Jerusalem (538 BCE) and allowed them to rebuild the temple in Jerusalem, a new and unifying form of Judaism emerged. This was characterized by the views and traditions of the returnees. They created a myth of “exile and return”, an idea that all the people had been carried away and returned. This, despite the fact that a large part of Juda’s lower strata of society had remained in the country, and that a large part of the abducted chose to stay in Babylonia. The more popular religion, which was still practiced across the country, was strongly condemned. In post-exilic houses, terracotta figures and Egyptian symbols no longer exist.

For nearly two hundred years, Judah was a poor province of the great Persian Empire. For about. 515 BCE the new temple was finished, probably an easier version than the old one. The covenant casket had disappeared, but the temple cult once again became the common national gathering place, where the priests (Kohen/Kohanim) stood for the sacrifices. From now on, the prestige became increasingly important. The temple also became the province’s financial center. It was also here that the people met for the big holidays. Priests and Levites was traditionally divided into 24 guards, serving one week at a time, twice a year. Now the rest of the people were also divided into such guards, where representatives of the different regions should be present to attend the sacrifices, so as to give the whole people participation in the rituals.

Much also indicates that the books of Moses were edited in the time around and after the exile. Scientists believe that parts of the book of Psalms and prophet literature were also written down and made available for study and interpretation, including by people living outside Judah. Probably literacy has also become more widespread among the people. In Nehemiah 8, 1–5 (AD 400), we hear that Ezra the printer is reading from the Law (Torah one) for the people. Ezra’s book tells of how he forces the people to divorce their “foreign wives” and warns families not to marry their children to those of the country’s inhabitants who are not among the returners. Nehemiah’s book also tells about how Nehemiah restores the covenant between God and the people, by drawing up a written agreement signed by all the chiefs, priests, and Levites. All the people should now practice the same kind of cult and adhere to the same religious laws.

Gradually, the books of Moses were regarded as an unchanging and divine revelation text. At a very early stage, however, the scholars must have realized that the texts had to be interpreted and explained in order to keep their relevance through changing times. It was also important to derive moral and ethical principles from the many stories in the Bible texts. The purpose was to make it possible to live according to the covenant that was believed to have already been made on Mount Sinai. Later Jewish tradition traces this interpretation tradition back to Joshua. It should then have passed on to the “elders,” and from them to the prophets. After the exile, the tradition is to be continued by “The Great Assembly,” a group of scholars led by printer Ezra. We do not have much information about the range of intermediaries from the 400s BCE. up to maccabees time almost three hundred years later.

In the time leading up to the destruction of the temple in the year 70 AD, well-known academies (jeshiva’s) were gradually established in which the scholars further developed both the laws, daily ordinances and ethics (see Hillel, Shammai). In the later times of the Second Temple, the Jewish Sanhedrin also remained in the courtyard of the Temple. It also became more and more common to attend synagogues for prayer and study. The foundation was laid for what was later called rabbinic Judaism. It was this one that took over when the temple cult ended and the Jews were each driven into exile.

Body and soul

In the time after the exile, notions of bodily resurrection arose, probably under the influence of Zoroastrianism. In the last centuries before the beginning of our era, the ideas of the immortality of the soul also came (Daniel 12). The new ideas were developed by the Pharisees and early rabbis, but must have been rejected by the clergy, the Sadducees. The scholars now focused increasingly on the fate of the individual and the individual after death. The belief in the resurrection of the dead is closely linked to the doctrine of punishment and reward. While previously God’s punishment was supposed to take place here on earth, a belief arose that the result of one’s actions would appear in the next life. The Pharisees began to use terms likeolam ha-ze (this world) and olam ha-ba (the world to come).

The ideas of the resurrection of the body and the soul also played a major role in many pious circles, e.g. among the essays, which most believe wrote and copied the Dead Sea Scrolls. In the time before the fall of the temple, an apocalyptic also developed, which especially unfolded in apocryphal writings. Most of these have not been recognized by the Holy Scriptures of Judaism.